You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

The dental hygienist plays a crucial role in patient care in the dental office and in many cases is the first provider to see patients, whether it be for the first patient visit or routine dental care. Dental hygienists are often the "eyes and ears" of the dental office and are in a unique position to be the first to identify systemic diseases as part of a comprehensive oral exam. Such early identification and subsequent referral for definitive diagnosis and care can lead to better overall health outcomes, improved oral health, and less overall financial burden to the patient. The dental office has untapped potential to serve as a pathway for screening patients who may not receive non-emergent physician visits. It is important for dental hygienists to recognize symptoms of common undiagnosed or improperly managed systemic disease, such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and mental health disorders. Early identification can significantly improve the healthcare provided to the communities served by the dental office, and, with proper protocols, identifying patients that are at risk of chronic diseases is efficient and effective. Furthermore, given the known impacts of such chronic diseases on oral wellness, improved systemic health has the potential to improve oral health as well.

Prevalence and Economic Impact of Chronic Diseases

The cost savings of early screening for chronic diseases is evident at the individual patient level, for the dental office, and for the community. Early detection of chronic diseases or identifying patients at risk can prevent a lifetime cost of medications and reduce the risk of long-term adverse events associated with poor control and/or delayed diagnoses. For example, patients diagnosed with diabetes mellitus spend almost $17,000 annually on medical expenses, with about $10,000 of it attributed to the management and complications of diabetes mellitus. On average, the healthcare expenditures of patients with diabetes are 2.3-fold greater than those without diabetes.1 Recent studies have found that providing appropriate oral healthcare to patients with both diabetes mellitus and periodontitis can also further reduce their medical expenditures by about $2,500 annually.2 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data reveal that oral health and overall health was linked in older adults.3 Oral disease and systemic diseases such as coronary heart disease, diabetes, asthma, and liver disease have been linked.3 At the community level, much of the economic burden of healthcare costs is distributed to employees and taxpayers. For example, it is estimated that the total societal cost of diabetes in 2017 was $327 billion, including $90 billion in reduced productivity within the economy.1 This number is likely an underestimation as approximately 8.7 million Americans (or up to 23% of adults with diabetes) are undiagnosed.4,5 Avoidable utilization of emergency department services and unrecognized complications in undiagnosed individuals also contribute to indirect costs.1 It is estimated that screening for chronic diseases in the dental office could reduce healthcare costs by up to $102.6 million annually.6 Dental healthcare professionals have a unique opportunity to not only identify patients at high risk to improve their individual health, but to lessen the already overwhelming burden of chronic diseases on our health system.

Systemic Disease Targets for Dental Office Screening

Dental diseases, such as caries and periodontal disease, continue to be highly prevalent in the US population. Although there has been a decrease over the past century, delivery of preventive and interventional oral care is critical for maintaining the wellness of the patient population. According to recent NHANES data, dental caries was still present in a majority of patients, with an estimate of 9.3 mean decayed missing and/or filled teeth (DMFT) in adults aged 20-64 years.7 This number nearly doubles when looking at patients older than 65 and of low social economic status.8 Similar to dental caries, prevalence of periodontal disease has seen a decline; however, current surveys still identify periodontitis in approximately 42% of US adults over the age of 30, with 7.8% having severe periodontitis.9 In addition, approximately 27 million Americans visit their dentist but not their physician annually.10 With many of these patients seeking care through the dental office multiple times a year, this presents an opportunity to emphasize overall health, screen for chronic diseases, and refer these patients to primary healthcare providers for further diagnosis and treatment.

Cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and mental health disorders are systemic diseases that have a significant impact on a patients' well-being, and they have some of the most cost-effective screening methods. Early identification of these chronic diseases can lead to reversal or arrest of disease progression in some cases and may result in more affordable and predictable management options when compared with later diagnosis.11 Recent studies evaluating patients that had newly been enrolled in the Affordable Care Act found that about 37.7% of patients had undiagnosed hypertension.12 The prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes is also high, ranging from 9.5% to 23% of all diabetics (up to 3.4% of the total US population).13 The true number of individuals with undiagnosed chronic disease may be higher. In many patients, dental healthcare professionals may have more regular interactions for routine, nonemergent care and this could allow an opportunity to evaluate, screen, and refer patients who can then benefit from diagnosis and treatment of disease.

Systemic Disease Screening in the Dental Office

To facilitate early detection of chronic diseases, screening can be included not only in the new patient intake form but also as part of a standard procedure for all patient visits. As part of a comprehensive exam, the patient intake form should contain questions that ask about risk factors for disease, including demographic data, alcohol and tobacco consumption, familial history of chronic diseases, self-reported physical activity levels, self-reported nutritional intake, current symptomatology, and self-reported mental health status. The patients' answers can be updated with yearly periodic exams. With every periodic exam, anthropomorphic measurements, including height and weight, can be performed to determine risk for malnutrition or obesity. At each dental visit, blood pressure and pulse rates should be taken in order to deliver safe dental care, but such measurements can also provide insight for patients and physicians to help determine undiagnosed and/or incomplete management of hypertension. Patients that have one or more self-reported risk factors can then be further evaluated by assessing glycemic control via a glucometer and/or chairside HbA1c screening device. Such low-cost, impactful tools can be used to further determine patients' risk for chronic disease and whether a referral should be made or treatment deferred (Figure 1). Additional resources regarding the diagnostic tools that are available to health professionals for such screenings are listed at the end of this article.

Cardiovascular Screening

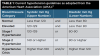

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide, with an estimated 31% of all deaths associated with some cardiovascular diseases, specifically acute myocardial infarction and strokes.14 Measuring blood pressure should be done with every patient visit, not only to screen patients, but also to evaluate the risk of proceeding with procedures that can elevate blood pressure to unsafe levels. Elevated blood pressure can often go unnoticed without accurate measurement as symptoms tend to be absent or very mild until patients present with hypertensive crisis. It should be noted that patients with consistently high blood pressure are at risk for permanent or even fatal organ failure. However, with early detection, hypertension can be well managed with lifestyle changes and pharmaceuticals. Blood pressure measurements can be taken with a manual cuff or electric cuff, and, if greater than 160/100 mm Hg, no elective dental treatment should be done and the dental patient should be referred for consultation with a physician.15 Stage 1 hypertension is associated a two-fold increase in cardiovascular complications when compared with normal blood pressure.16 Patients with blood pressure measurements that place them into a hypertensive crisis should be immediately referred to emergency care and only after control of hypertension and release from emergency care should dental care be continued. Table 1 outlines the categories of hypertension according to the American Heart Association.17

Diabetes

Diabetes is a serious chronic disease that can result in significant complications when sub optimally controlled, but with close monitoring, early detection, and appropriate behavioral and pharmacological management, disease progression can be halted, and diabetes complications can be limited and/or avoided. There are two forms of diabetes mellitus: Type 1 Diabetes, previously known as insulin-dependent diabetes, and Type 2 Diabetes, previously known as "adult-onset diabetes." Type 1 Diabetes is an autoimmune disorder that occurs due to the destruction of beta-islet cells in the pancreas and ultimately results in a lack of endogenous insulin production. Type 2 Diabetes, which accounts for about 90% of cases, is due to insulin resistance and may be managed by diet and exercise changes, oral medications, non-insulin injectable medications, and/or insulin supplementation. Both forms of the disease lead to hyperglycemia, which if left untreated, can cause permanent damage to multiple organ systems such as the vasculature, heart, kidneys, liver, nervous system, retinas, and oral tissues.18 Diabetes has several risk factors that increase the likelihood of development during a patient's lifetime. Dental healthcare professionals should consider screening patients who have any of the following15,19-21:

• >35 years of age

• No history of diabetes

• No medication used for impairing glucose metabolism

• No visit to a primary care physician in the prior 12 months

• Stage 1 Hypertension (130 to 139/80 to 89 mm Hg)

• A BMI greater than 25 kg/m2

• Have been told that they are prediabetic

• Have first-degree family members with diabetes

• High risk race/ethnicity (eg, African American, Hispanic or Latino, Native American, Asian American, Pacific Islander)

• Hyperlipidemia

• Periodontal disease

After identifying patients at risk, a casual blood glucose or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) test can be administered chairside and the current dental terminology (CDT) codes D0411 and D0412, respectively, can be used to document this screening. Such screening should not constitute a definitive diagnosis but should provide dental healthcare professionals information to aid in patient referral for laboratory testing, diagnosis, and management. Casual blood glucose test results of greater than 200mg/dl may indicate current significant hyperglycemia, and a chairside HbA1c value greater than 5.7% or 6.5% would indicate significant risk prediabetes and diabetes, respectively. Such results and a list of risk factors that the patient presents with should be included in any referral to an endocrinologist or primary care physician to aid in their assessment and diagnosis. More information can be found on the American Diabetes Association (ADA) Quick Guide.22

In summary, dental healthcare professionals are not expected to diagnose diabetes, but recognizing risk factors and in-office monitoring of blood glucose can improve oral and overall health outcomes and may alter patients' treatment planning for delivery of dental care.

Dietary Analysis

An integral part of a complete dental exam is assessing the nutrition and diet of the patient, because poor nutrition can result in elevated caries and poorer periodontal health and retard tissue healing.23,24 As dental healthcare professionals are well aware, dietary counseling is a cornerstone to caries prevention, and patients should be counseled about reducing sugar intake, rinsing with water after meals, and practicing good oral hygiene.25 Resources are available to oral health professionals through the ADA that give a good basis for recommendations.26 Practitioners should also be aware of and able to identify patients who show signs of malnourishment or obesity. An initial nutritional assessment-including assessment of the weight and height of the patient—should be performed to calculate the body mass index (BMI). If the measured BMI is less than 20.5; if the patient has lost weight in the past 3 months; or if their food intake was reduced in the past week, consider using a nutritional risk assessment screen and referring to a dietician who can better evaluate the patient.27 Malnutrition can result in poor wound healing following surgical procedures and, if identified early, can be addressed with nutritional support. Furthermore, such assessments, combined with certain oral symptoms, could help identify individuals who are suffering from eating disorders and could benefit from definitive diagnosis and treatment.28 If the measured BMI is greater than 30, further analysis of nutrition should be done as well as a referral for a primary care provider. Follow-up questions can include inquiring about physical activity, and recommendations can be made to engage in physical activity at least 2 to 4 times a week. Recent studies report that men and women who are more physically active have lower rates of cardiovascular disease, pulmonary dysfunction, sleep apnea, diabetes mellitus, and obesity.29 Even if weight loss is not a goal, increasing physical activity has significant systemic health benefits, and addressing dietary concerns can be one of the most cost-effective interventions to improve patients' health.

Mental Health Screening

It is well documented that poor mental health, such as anxiety, depression, and stress, have been linked to poorer oral health, increased risk of systemic diseases, cardiovascular disease, other chronic systemic disorders, and poorer oral hygiene practices.30 Patients with severe mental illnesses are 2.7 times more likely to lose all of their teeth when compared with the general population.28 Common risk factors associated with poor mental health include complicated grief, chronic sleep disturbance, loneliness, and a history of depression. Effects of poor mental health can be observed in the oral cavity and can include generalized untreated caries, erosion, and bruxism.28 The presence or absence of any risk factor does not imply disease but can be an indication for when to screen patients. Identifying patients at risk for depression and anxiety in the dental office can be done with the Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ8) (Figure 2). Additionally, there is the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) for older adults because elderly individuals have an overall lower prevalence of anxiety and depression than younger individuals, but the risk factors are different than seen in the general population.30 All positive screenings should be followed up with further assessment and referral to primary care. Additional resources on specific mental health topics can be found on the NIH National Institute of Mental Health website.31

Bidirectional Interprofessional Referral

Once a patient is determined to be at high risk for any chronic disease, a detailed, concise, and thorough medical referral should be written, given to the patient, and faxed/securely emailed/mailed to their primary care provider once a HIPAA release is signed. There are three main components to writing a medical referral: 1) Documentation of the findings identified, any screening tests performed, and discussion of the results that were determined by the dental healthcare professionals; 2) Discussion of dental and oral diagnoses and the associated treatment plan to address any oral conditions, including a description of potential risks; 3) Contact instructions for the physician to maintain good communication and next steps for collaboration to best manage the patient. A detailed report of the questions asked and test results can prepare the primary care provider to order more comprehensive tests to allow for definitive diagnoses. Open and ongoing communication between dental healthcare professionals and medical providers can allow for delivery of personalized care to optimize oral and overall health.

Conclusion

Screening for systemic diseases in the dental office is a time- and cost-effective method to identify patients at risk for chronic health diseases and drastically make a difference in their well-being. As healthcare professionals, it is our duty to stay up to date on potential indicators of disease, warn our patients of potential risks, and guide them to resources that can help them. Doing so will not only make an impact on the individual patient, but on the entire community.

About the Authors

Lincoln Nguyen, DDS

PGY3 Periodontology Resident

University of Alabama at Birmingham

Birmingham, Alabama

Maria L. Geisinger, DDS, MS

Professor

University of Alabama at Birmingham

Department of Periodontology

Birmingham, Alabama

References

1. American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):917-928.

2. Thakkar-Samtani M, Heaton LJ, Kelly AL, et al. Periodontal treatment associated with decreased diabetes mellitus-related treatment costs: an analysis of dental and medical claims data. J Am Dent Assoc. 2023;154(4):283-292.e1.

3. Hung M, Moffat R, Gill G, et al. Oral health as a gateway to overall health and well-being: surveillance of the geriatric population in the United States. Spec Care Dentist. 2019;39(4):354-361.

4. Michaeli E, Weinberg I, Nahlieli O. Dental implants in the diabetic patient: systemic and rehabilitative considerations. Quintessence Int. 2009;40(8):639-645.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report: estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html. Updated November 29, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023.

6. Nasseh K, Greenberg B, Vujicic M, Glick M. The effect of chairside chronic disease screenings by oral health professionals on health care costs. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(4):744-750.

7. Dental caries (tooth decay) in adults (ages 20 to 64 years). NIH National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research website. https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/dental-caries/adults. Updated November 2022. Accessed December 14, 2023.

8. Rozier RG, White BA, Slade GD. Trends in oral diseases in the U.S. population. J Dent Educ. 2017;81(8):eS97-eS109.

9. Eke PI, Thornton-Evans GO, Wei L, et al. Periodontitis in US adults: national health and nutrition examination survey 2009-2014. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149(7):576-588.e6.

10. Vujicic M, Nasseh K. A decade in dental care utilization among adults and children (2001-2010). Health Serv Res. 2014;49(2):460-480.

11. Fragala MS, Shiffman D, Birse CE. Population health screenings for the prevention of chronic disease progression. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(11):548-553.

12. Huguet N, Larson A, Angier H, et al. Rates of undiagnosed hypertension and diagnosed hypertension without anti-hypertensive medication following the Affordable Care Act. Am J Hypertens. 2021;34(9):989-998.

13. Fang M, Wang D, Coresh J, Selvin E. Undiagnosed diabetes in U.S. adults: prevalence and trends. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(9):1994-2002.

14. Cardiovascular diseases. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases. Accessed December 21, 2023.

15. Patton LL, Glick M, eds. The ADA Practical Guide to Patients with Medical Conditions. 1st ed. Wiley; 2015.

16. Peng X, Jin C, Song Q, et al. Stage 1 hypertension and the 10-year and lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease: a prospective real-world study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(7):e028762.

17. Understanding blood pressure readings. American Heart Association website. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/understanding-blood-pressure-readings. Updated May 30, 2023. Accessed December 21, 2023.

18. World Health Organization. Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. World Health Organization; 2019. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/325182.

19. Cunha-Vaz J. Diabetic Retinopathy. World Scientific; 2010.

20. US Preventive Services Task Force; Davidson KW, Barry MJ, et al. Screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;326(8):736-743.

21. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2011. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 1):S11-S61.

22. D0411 and D0412 - ADA quick guide to in-office monitoring and documenting patient blood glucose and HbA1C level. American Dental Association website. https://www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/publications/cdt/cdt_d0411_d0412_guide_v1_2019jan02.pdf. Published January 1, 2019. Accessed December 14, 2023.

23. Stechmiller JK. Understanding the role of nutrition and wound healing. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25(1):61-68.

24. Pitts NB, Zero DT, Marsh PD, et al. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17030.

25. Home oral care. American Dental Association website. https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/home-care. Updated December 30, 2022. Accessed December 21, 2023.

26. Nutrition and oral health. American Dental Association website. https://www.ada.org/en/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/nutrition-and-oral-health. Updated August 30, 2023. Accessed December 21, 2023.

27. Reber E, Gomes F, Vasiloglou MF, et al. Nutritional risk screening and assessment. J Clin Med. 2019;8(7):1065.

28. Kisely S. No mental health without oral health. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(5):277-282.

29. Marques A, Santos T, Martins J, et al. The association between physical activity and chronic diseases in European adults. Eur J Sport Sci. 2018;18(1):140-149.

30. Ball J, Darby I. Mental health and periodontal and peri-implant diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2022;90(1):106-124.

31. Brochures and fact sheets. NIH National Institute of Mental Health website. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications. Accessed December 14, 2023.